Code

import pandas as pd

import numpy as np

import scipy as sp

import plotly.express as px

import seaborn as snsSo far in this course, we’ve focused on supervised learning techniques that create a function to map inputs (features) to labelled outputs. Regression and classification are two main examples, where the output value of regression is quantitative while the output value of classification is categorical.

Today, we’ll introduce an unsupervised learning technique called PCA. Unlike supervised learning, unsupervised learning is applied to unlabeled data. Because we have features but no labels, we aim to identify patterns in those features. Principal Component Analysis (PCA) is a linear technique for dimensionality reduction, and PCA relies on a linear algebra algorithm called Singular Value Decomposition, which we will discuss more in the next lecture.

Visualization can help us identify clusters or patterns in our dataset, and it can give us an intuition about our data and how to clean it for the model. For this demo, we’ll return to the MPG dataset from Lecture 19 and see how far we can push visualization for multiple features.

import pandas as pd

import numpy as np

import scipy as sp

import plotly.express as px

import seaborn as snsmpg = sns.load_dataset("mpg").dropna()

mpg.head()| mpg | cylinders | displacement | horsepower | weight | acceleration | model_year | origin | name | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 18.0 | 8 | 307.0 | 130.0 | 3504 | 12.0 | 70 | usa | chevrolet chevelle malibu |

| 1 | 15.0 | 8 | 350.0 | 165.0 | 3693 | 11.5 | 70 | usa | buick skylark 320 |

| 2 | 18.0 | 8 | 318.0 | 150.0 | 3436 | 11.0 | 70 | usa | plymouth satellite |

| 3 | 16.0 | 8 | 304.0 | 150.0 | 3433 | 12.0 | 70 | usa | amc rebel sst |

| 4 | 17.0 | 8 | 302.0 | 140.0 | 3449 | 10.5 | 70 | usa | ford torino |

We can plot one feature as a histogram to see it’s distribution. Since we only plot one feature, we consider this a 1-dimensional plot.

px.histogram(mpg, x="displacement")We can also visualize two features (2-dimensional scatter plot):

px.scatter(mpg, x="displacement", y="horsepower")Three features (3-dimensional scatter plot):

fig = px.scatter_3d(mpg, x="displacement", y="horsepower", z="weight",

width=800, height=800)

fig.update_traces(marker=dict(size=3))We can even push to 4 features using a 3D scatter plot and a colorbar:

fig = px.scatter_3d(mpg, x="displacement",

y="horsepower",

z="weight",

color="model_year",

width=800, height=800,

opacity=.7)

fig.update_traces(marker=dict(size=5))Visualizing 5 features is also possible if we make the scatter dots unique to the datapoint’s origin.

fig = px.scatter_3d(mpg, x="displacement",

y="horsepower",

z="weight",

color="model_year",

size="mpg",

symbol="origin",

width=900, height=800,

opacity=.7)

# hide color scale legend on the plotly fig

fig.update_layout(coloraxis_showscale=False)However, adding more features to our visualization can make our plot look messy and uninformative, and it can also be near impossible if we have a large number of features. The problem is that many datasets come with more than 5 features — hundreds, even. Is it still possible to visualize all those features?

Suppose we have a dataset of:

Let’s “rename” this in terms of linear algebra so that we can be more clear with our wording. Using linear algebra, we can view our matrix as:

The intrinsic dimension of a dataset is the minimal set of dimensions needed to approximately represent the data. In linear algebra terms, it is the dimension of the column space of a matrix, or the number of linearly independent columns in a matrix; this is equivalently called the rank of a matrix.

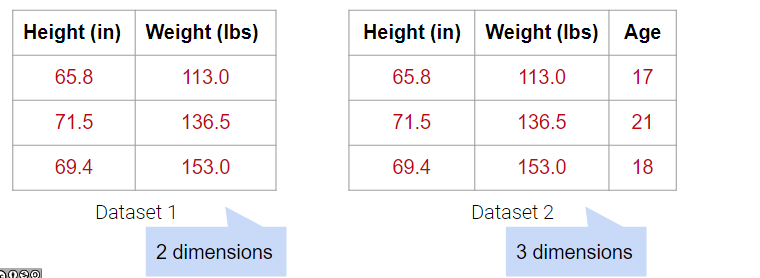

In the examples below, Dataset 1 has 2 dimensions because it has 2 linearly independent columns. Similarly, Dataset 2 has 3 dimensions because it has 3 linearly independent columns.

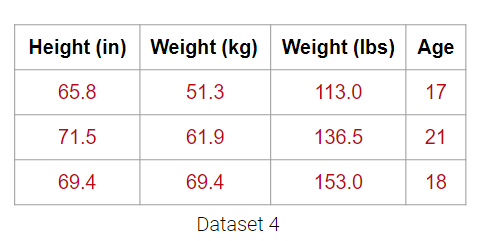

What about Dataset 3 below?

It may be tempting to say that it has 4 dimensions, but the Weight (lbs) column is actually just a linear transformation of the Weight (kg) column. Thus, no new information is captured, and the matrix of our dataset has a (column) rank of 3! Therefore, despite having 4 columns, we still say that this data is 3-dimensional.

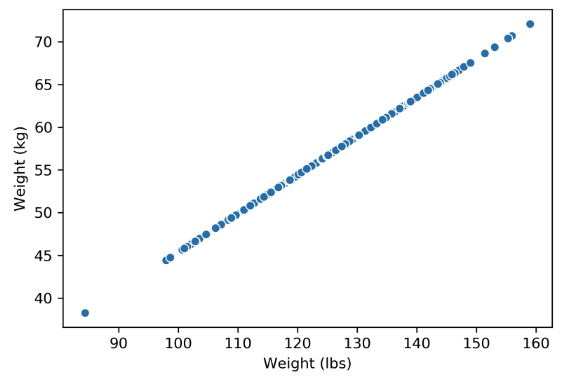

Plotting the weight columns together reveals the key visual intuition. While the two columns visually span a 2D space as a line, the data does not deviate at all from that singular line. This means that one of the weight columns is redundant! Even given the option to cover the whole 2D space, the data below does not. It might as well not have this dimension, which is why we still do not consider the data below to span more than 1 dimension.

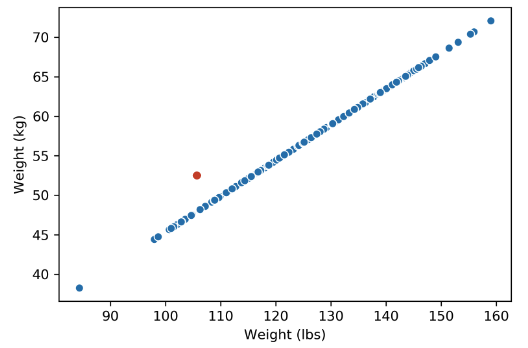

What happens when there are outliers? Below, we’ve added one outlier point to the dataset above, and just that one point is enough to change the rank of the matrix from 1 to 2 dimensions. However, the data is still approximately 1-dimensional.

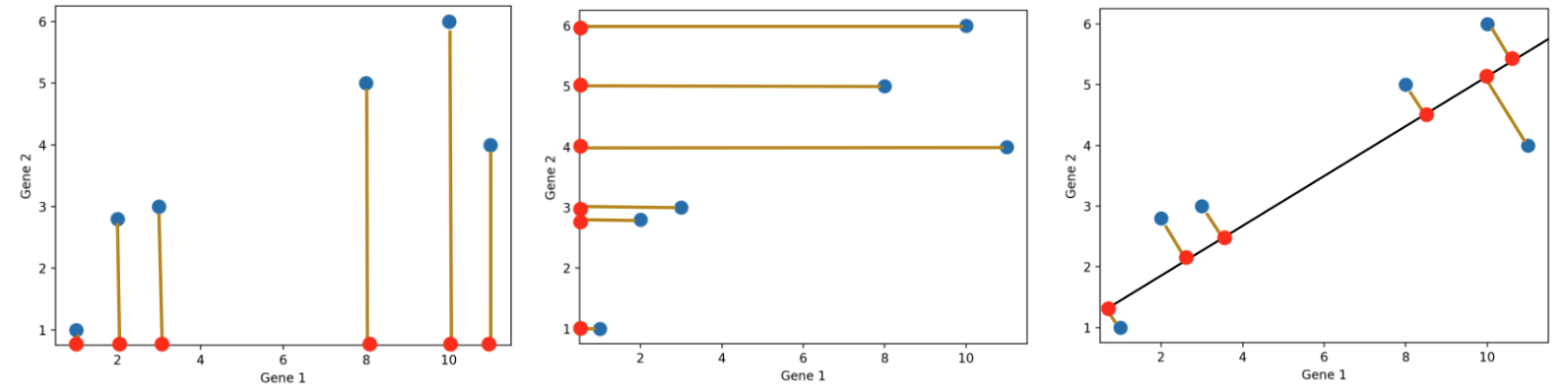

Dimensionality reduction is generally an approximation of the original data that’s achieved through matrix decomposition by projecting the data onto a desired dimension. In the example below, our original datapoints (blue dots) are 2-dimensional. We have a few choices if we want to project them down to 1-dimension: project them onto the \(x\)-axis (left), project them onto the \(y\)-axis (middle), or project them to a line \(mx + b\) (right). The resulting datapoints after the projection is shown in red. Which projection do you think is better? How can we calculate that?

In general, we want the projection which is the best approximation for the original data (the graph on the right). In other words, we want the projection that captures the most variance of the original data. In the next section, we’ll see how this is calculated.

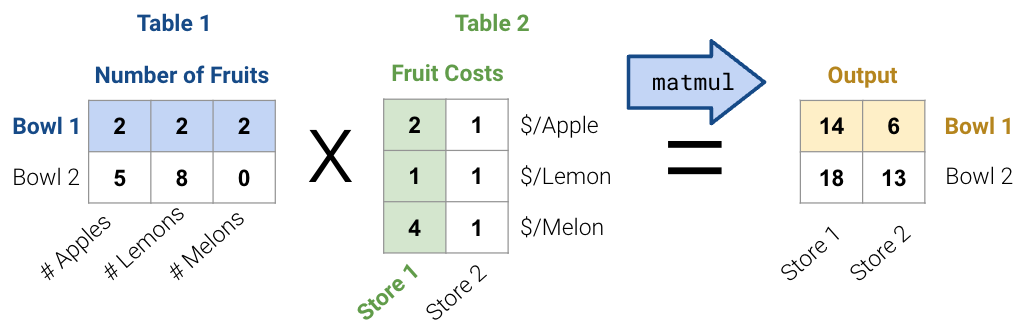

One linear technique for dimensionality reduction is matrix decomposition, which is closely tied to matrix multiplication. In this section, we will decompose our data matrix \(X\) into a lower-dimensional matrix \(Z\) that approximately recovers the original data when multiplied by \(W\).

First, consider the matrix multiplication example below:

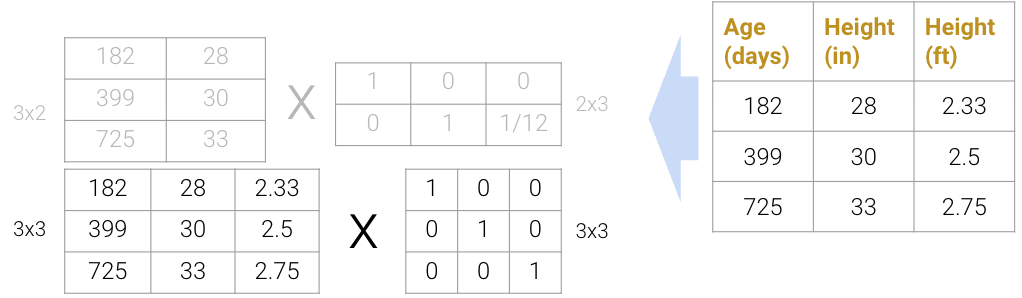

Matrix decomposition (a.k.a matrix factorization) is the opposite of matrix multiplication. Instead of multiplying two matrices, we want to decompose a single matrix into 2 separate matrices. Just like with real numbers, there are infinite ways to decompose a matrix into a product of two matrices. For example, \(9.9\) can be decomposed as \(1.1 * 9\), \(3.3 * 3\), \(1 * 9.9\), etc. Additionally, the sizes of the 2 decomposed matrices can vary drastically. In the example below, the first factorization (top) multiplies a \(3\times2\) matrix by a \(2\times3\) matrix while the second factorization (bottom) multiplies a \(3\times3\) matrix by a \(3\times3\) matrix; both result in the original matrix on the right.

We can even expand the \(3\times3\) matrices to \(3\times4\) and \(4\times3\) (shown below as the factorization on top), but this defeats the point of dimensionality reduction since we’re adding more “useless” dimensions.

On the flip side, we also can’t reduce the dimension to \(3\times1\) and \(1\times3\) (shown below as the factorization on the bottom); since the rank of the original matrix is greater than 1, this decomposition will not result in the original matrix.

In practice, we often work with datasets containing many features, so we usually want to construct decompositions where the dimensionality is below the rank of the original matrix. While this does not recover the data exactly, we can still provide approximate reconstructions of the matrix.

In the next section, we will discuss a method to automatically and approximately factorize data. This avoids redundant features and makes computation easier because we can train on less data. Since some approximations are better than others, we will also discuss how the method helps us capture a lot of information in a low number of dimensions.

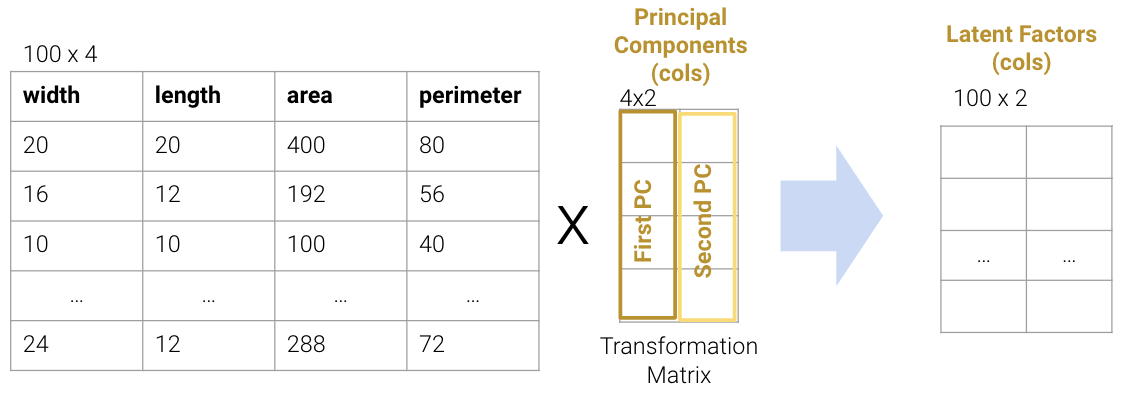

In PCA, our goal is to transform observations from high-dimensional data down to low dimensions (often 2, as most visualizations are 2D) through linear transformations. In other words, we want to find a linear transformation that creates a low-dimension representation that captures as much of the original data’s variability as possible.

Each column of the transformation matrix is a prinicipal component that describes the basic directions of the data when represented in lower-dimensional space. The columns of the new lower-dimension representation are called the latent factors, and we often work with these to represent and visualize the data. We’ll discuss more about these two terms in a bit.

We often perform PCA during the Exploratory Data Analysis (EDA) stage of our data science lifecycle when we don’t know what model to use. It helps us with:

There are two equivalent ways of framing PCA:

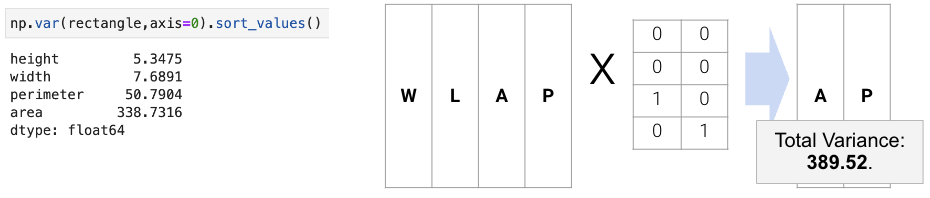

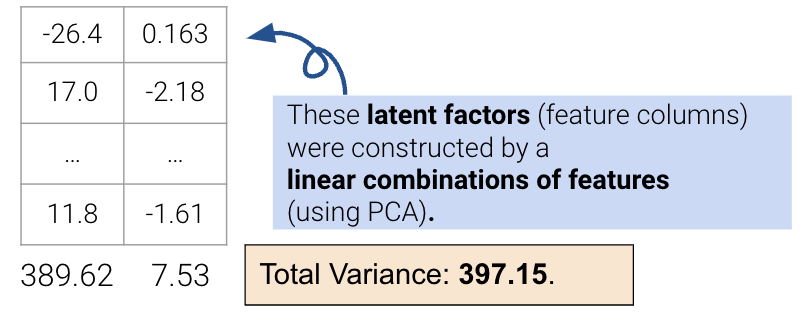

To execute the first approach of variance maximization framing (more common), we can find the variances of each attribute with np.var and then keep the \(k\) attributes with the highest variance. For example, if we are working with data that has the features width, length, area, and perimeter, we can compute the total variance as the sum of the variance in each column. The total variance would be 402.56, and we want to find a representation which captures as much of the original data’s total variance as possible. Here, we choose area and perimeter which captures 389.52 of the original 402.56.

However, this approach limits us to work with attributes individually; it cannot resolve collinearity, and we cannot combine features. The second approach uses PCA to construct latent factors with the most variance in the data (even higher than the first approach) using linear combinations of features.

We’ll describe the procedure for this second approach in the next section.

To perform PCA on a matrix:

The \(k\) principal components capture the most variance of any \(k\)-dimensional reduction of the data matrix. In the example below from Stack Exchange, maximizing variance means spreading out the red dots, and minimizing error (the projections) means making red lines short.

In this section, we will derive PCA keeping the following goal in mind: minimize the reconstruction loss for our matrix factorization model. You are not expected to be able to be able to redo this derivation, but understanding the derivation may help with future assignments.

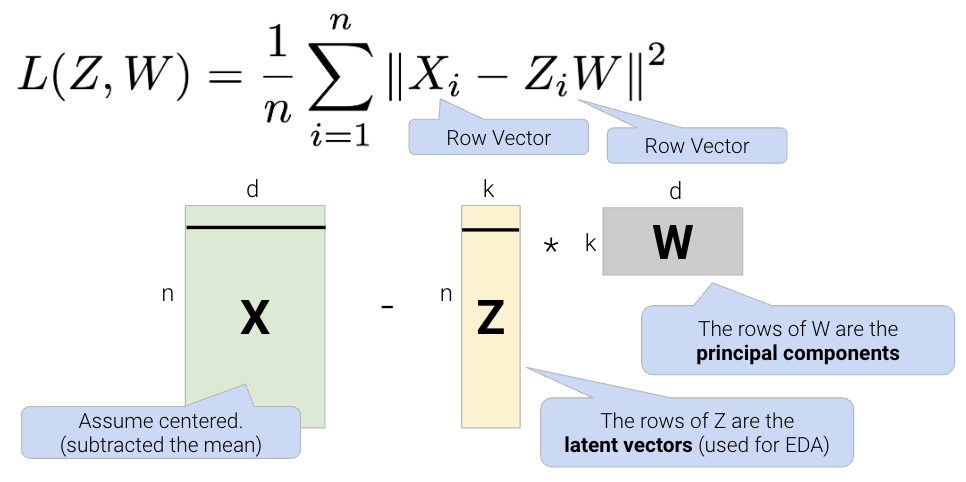

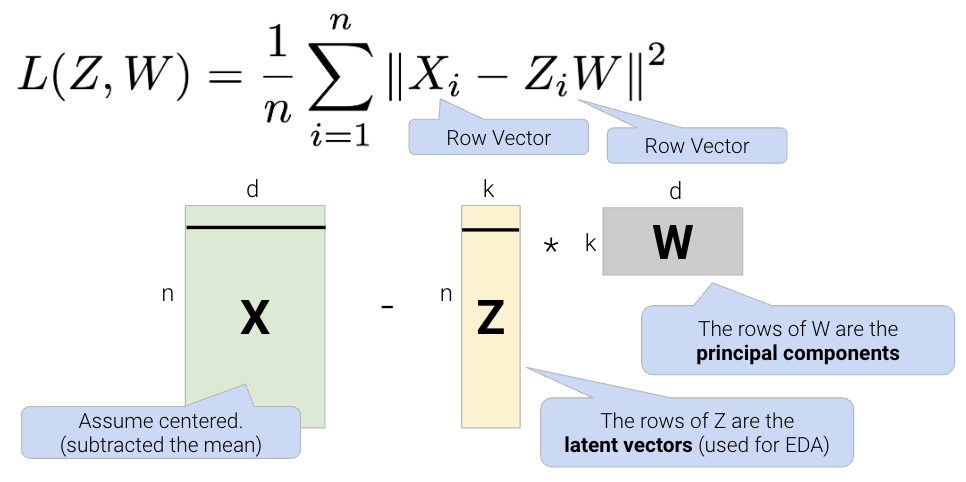

Given a matrix \(X\) with \(n\) rows and \(d\) columns, our goal is to find its best decomposition such that \[X \approx Z W\] Z has \(n\) rows and \(k\) columns; W has \(k\) rows and \(d\) columns. To measure the accuracy of our reconstruction, we define the reconstruction loss below, where \(X_i\) is the row vector of \(X\), and \(Z_i\) is the row vector of \(Z\):

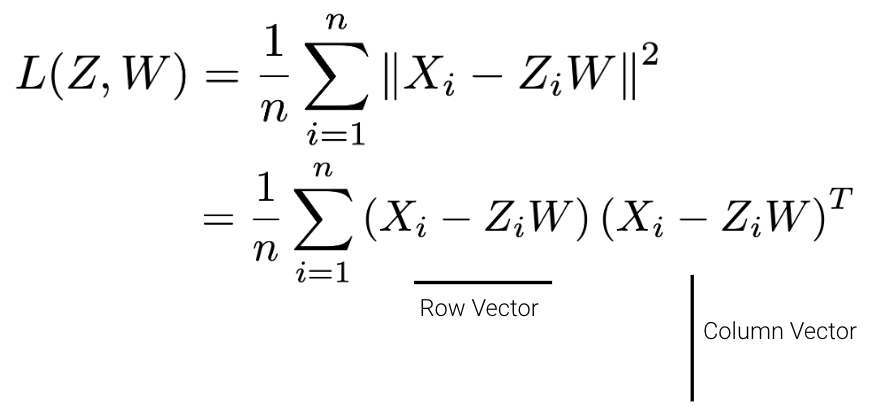

We can then rewrite the norm squared as the matrix product of a row vector and a column vector.

There are many solutions to the above, so let’s constrain our model such that \(W\) is a row-orthonormal matrix (i.e. \(WW^T=I\)) where the rows of \(W\) are our principal components.

In our derivation, let’s first work with the case where \(k=1\). Here Z will be an \(n \times 1\) vector and W will be a \(1 \times d\) vector.

\[\begin{aligned} L(z,w) &= \frac{1}{n}\sum_{i=1}^{n}(X_i - z_{i}w)(X_i - z_{i}w)^T \\ &= \frac{1}{n}\sum_{i=1}^{n}(X_{i}X_{i}^T - 2z_{i}X_{i}w^T + z_{i}^{2}ww^T) \ \ \ \text{(expand the loss)} \\ &= \frac{1}{n}\sum_{i=1}^{n}(-2z_{i}X_{i}w^T + z_{i}^{2}) \ \ \ \text{(First term is constant and }ww^T=1\text{ by orthonormality)} \\ \end{aligned}\]

Now, we can take the derivative with respect to \(z_i\), set the derivative equal to 0, and solve for \(z_i\). \[\begin{aligned} \frac{\partial{L(z,w)}}{\partial{z_i}} &= \frac{1}{n}(-2X_{i}w^T + 2z_{i}) \\ z_i &= X_iw^T \end{aligned}\]

This tells us that we can compute \(z\) by projecting onto \(w\). We can now substitute our solution for \(z_i\) in our loss function:

\[\begin{aligned} L(z,w) &= \frac{1}{n}\sum_{i=1}^{n}(-2z_{i}X_{i}w^T + z_{i}^{2}) \\ L(z=Xw^T,w) &= \frac{1}{n}\sum_{i=1}^{n}(-2X_iw^TX_{i}w^T + (X_iw^T)^{2}) \\ &= \frac{1}{n}\sum_{i=1}^{n}(-X_iw^TX_{i}w^T) \\ &= \frac{1}{n}\sum_{i=1}^{n}(-wX_{i}^TX_{i}w^T) \hspace{1cm} \textcolor{green}{\text{Algebra}}\\ &= -w\frac{1}{n}\sum_{i=1}^{n}(X_i^TX_{i})w^T \\ &= -w\Sigma w^T \hspace{2cm} \textcolor{green}{\text{Definition of Covariance ($\Sigma$)}} \end{aligned}\]

Now, we need to minimize our loss with respect to \(w\). Since we have a negative sign, one way we can do this is by making \(w\) really big. However, we also have the orthonormality constraint \(ww^T=1\). To incorporate this constraint into the equation, we can add a Lagrange multiplier, \(\lambda\). Note that lagrangian multipliers are out of scope for Data 100.

\[ L(w,\lambda) = -w\Sigma w^T + \lambda(ww^T-1) \]

Taking the derivative with respect to \(w\) and setting equal to zero, \[\begin{aligned} \frac{\partial{L(w,\lambda)}}{\partial{w}} &= -2\Sigma w^T + 2\lambda w^T \\ -2\Sigma w^T + 2\lambda w^T &= 0 \\ \Sigma w^T &= \lambda w^T \\ \end{aligned}\]

This result implies that:

This derivation can inductively be used for the next (second) principal component (not shown).

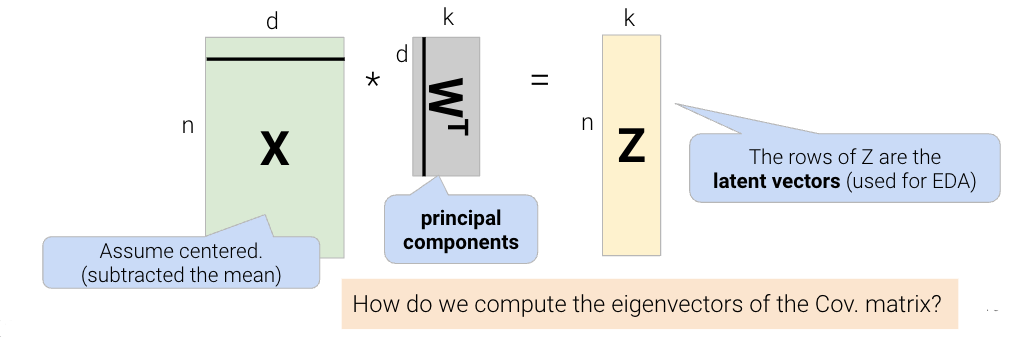

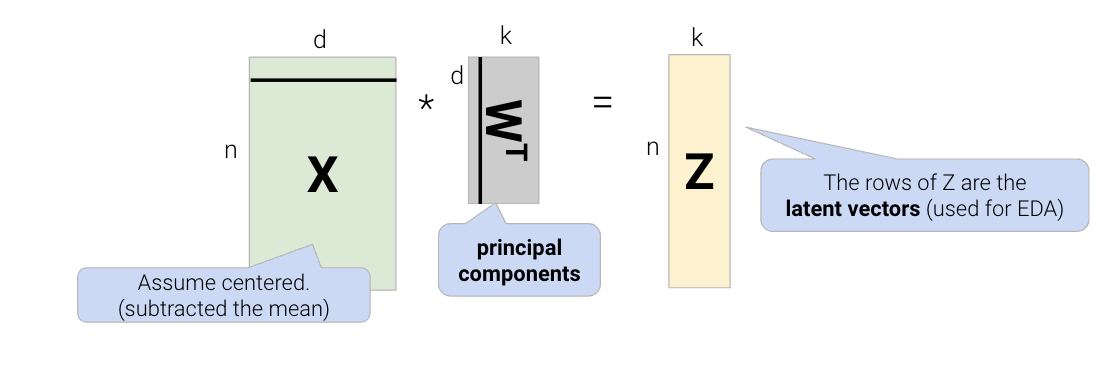

The final takeaway from this derivation is that the principal components are the eigenvectors with the largest eigenvalues of the covariance matrix. These are the directions of the maximum variance of the data. We can construct the latent factors (the Z matrix) by projecting the centered data X onto the principal component vectors:

We often work with high-dimensional data that contain many columns/features. Given all these dimensions, this data can be difficult to visualize and model. However, not all the data in this high-dimensional space is useful — there could be repeated features or outliers that make the data seem more complex than it really is. The most concise representation of high-dimensional data is its intrinsic dimension.

Our goal with this lecture is to use dimensionality reduction to find the intrinsic dimension of a high-dimensional dataset. In other words, we want to find a smaller set of new features/columns that approximates the original data well without losing that much information. This is especially useful because this smaller set of features allows us to better visualize the data and do EDA to understand which modeling techniques would fit the data well. Let’s treat this as a matrix factorization problem, and review what we covered in the previous lecture.

In order to find the intrinsic dimension of a high-dimensional dataset, we’ll use techniques from linear algebra. Suppose we have a high-dimensional dataset, \(X\), that has \(n\) rows and \(d\) columns. We want to factor (split) \(X \in \mathbb{R}^{n \times d}\) into two matrices, \(Z \in \mathbb{R}^{n \times k}\) and \(W \in \mathbb{R}^{k \times d}\): \[X \approx ZW\]

We can reframe this problem as a loss function, minimizing difference between \(X\) and \(ZW\): \[L(Z, W) = \frac{1}{n}\sum_{i=1}^{n}||X_i - Z_i W||^2\]

Breaking down the variables in this formula:

Using calculus and optimization techniques (take EECS 127 if you’re interested!), we find that this loss is minimized when \[Z = XW^T\] The proof for this is out of scope for Data 100, but for those who are interested, we:

Take a look at the previous lecture note for the full proof. This gives us a very cool result of \[\Sigma w^T = \lambda w^T\]

\(\Sigma\) is the covariance matrix of \(X\). The equation above implies that:

This tells us that the principal components (rows of \(W\)) are the eigenvectors with the largest eigenvalues of the covariance matrix \(\Sigma\). Thus, principal components represent the directions of maximum variance in the data. We can construct the latent factors, or the \(Z\) matrix, by projecting the centered data \(X\) onto the principal component vectors, \(W^T\).

But how do we compute the eigenvectors of \(\Sigma\)? Let’s dive into SVD to answer this question.

Singular value decomposition (SVD) is an important concept in linear algebra. Since this class requires a linear algebra course (MATH 54, MATH 56, or EECS 16A) as a pre/co-requisite, we assume you have taken or are taking a linear algebra course, so we won’t explain SVD in its entirety. In particular, we will not prove why SVD is a valid decomposition of rectangular matrices.

We will not dive deep into the theory and details of SVD. Instead, we will only cover what is needed for a data science interpretation. If you’d like more information, check out EECS 16B Note 14 and EECS 16B Note 15.

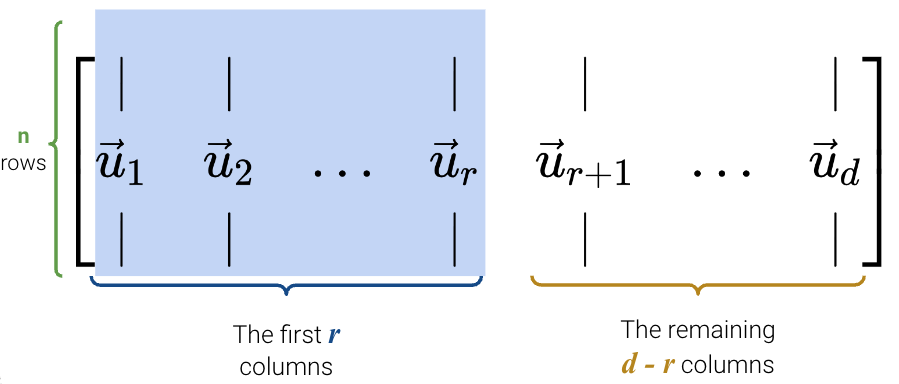

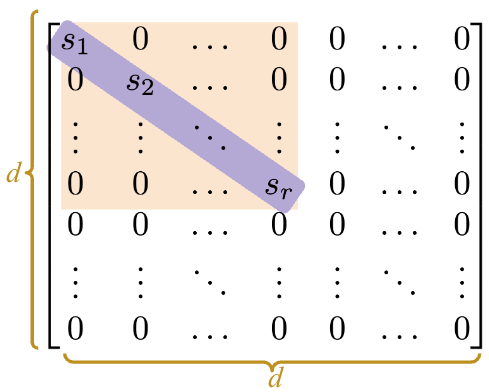

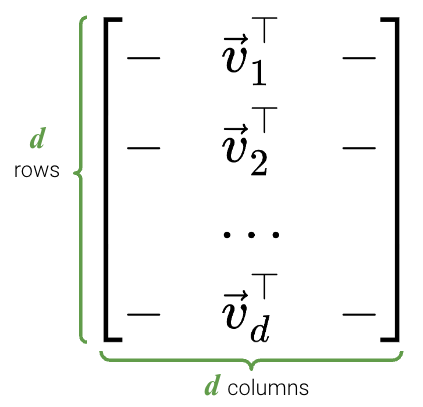

Singular value decomposition (SVD) describes a matrix \(X\)’s decomposition into three matrices: \[ X = U S V^T \]

Let’s break down each of these terms one by one.

Here is a proof that \(U\) consists of the eigenvectors of \(XX^T\): \[\begin{align} XX^T &= USV^T (USV^T)^T \\ &= USV^T V S^T U^T \\ &= USS^T U^T \end{align}\]

Now right multiply by \(U\): \[\begin{align} XX^T U &= US S^T U^T U \\ &= US S^T \end{align}\]

Just like before, here is a proof that \(V\) consists of the eigenvectors of \(X^TX\): \[\begin{align} X^TX &= (USV^T)^T USV^T \\ &= V S^T U^T USV^T \\ &= VS^TS V^T \end{align}\]

Now right multiply by \(V\): \[\begin{align} X^TX V &= VS^T S V^T V \\ &= VS^T S \end{align}\]

NumPyFor this demo, we’ll work with a rectangular dataset containing \(n=100\) rows and \(d=4\) columns.

import pandas as pd

import seaborn as sns

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import numpy as np

np.random.seed(23) # kallisti

plt.rcParams["figure.figsize"] = (4, 4)

plt.rcParams["figure.dpi"] = 150

sns.set()

rectangle = pd.read_csv("data/rectangle_data.csv")

rectangle.head(5)| width | height | area | perimeter | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 8 | 6 | 48 | 28 |

| 1 | 2 | 4 | 8 | 12 |

| 2 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 8 |

| 3 | 9 | 3 | 27 | 24 |

| 4 | 9 | 8 | 72 | 34 |

In NumPy, the SVD decomposition function can be called with np.linalg.svd (documentation). There are multiple versions of SVD; to get the version that we will follow, we need to set the full_matrices parameter to False.

U, S, Vt = np.linalg.svd(rectangle, full_matrices=False)First, let’s examine U. As we can see, it’s dimensions are \(n \times d\).

U.shape(100, 4)The first 5 rows of U are shown below.

pd.DataFrame(U).head(5)| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | -0.155151 | 0.064830 | -0.029935 | 0.967868 |

| 1 | -0.038370 | -0.089155 | 0.062019 | -0.151231 |

| 2 | -0.020357 | -0.081138 | 0.058997 | 0.003355 |

| 3 | -0.101519 | -0.076203 | -0.148160 | 0.006977 |

| 4 | -0.218973 | 0.206423 | 0.007274 | -0.042254 |

\(S\) is a little different in NumPy. Since the only useful values in the diagonal matrix \(S\) are the singular values on the diagonal axis, only those values are returned and they are stored in an array.

Our rectangle_data has a rank of \(3\), so we should have 3 non-zero singular values, sorted from largest to smallest.

Sarray([3.62932568e+02, 6.29904732e+01, 2.56544651e+01, 1.75309971e-14])It seems like we have 4 non-zero values instead of 3, but notice that the last value is so small (\(10^{-15}\)) that it’s practically \(0\). Hence, we can round the values to get 3 singular values.

np.round(S)array([363., 63., 26., 0.])To get S in matrix format, we use np.diag.

Sm = np.diag(S)

Smarray([[3.62932568e+02, 0.00000000e+00, 0.00000000e+00, 0.00000000e+00],

[0.00000000e+00, 6.29904732e+01, 0.00000000e+00, 0.00000000e+00],

[0.00000000e+00, 0.00000000e+00, 2.56544651e+01, 0.00000000e+00],

[0.00000000e+00, 0.00000000e+00, 0.00000000e+00, 1.75309971e-14]])Finally, we can see that Vt is indeed a \(d \times d\) matrix.

Vt.shape(4, 4)pd.DataFrame(Vt)| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | -0.146436 | -0.129942 | -8.100201e-01 | -0.552756 |

| 1 | -0.192736 | -0.189128 | 5.863482e-01 | -0.763727 |

| 2 | -0.704957 | 0.709155 | 7.951614e-03 | 0.008396 |

| 3 | -0.666667 | -0.666667 | -8.701245e-17 | 0.333333 |

To check that this SVD is a valid decomposition, we can reverse it and see if it matches our original table (it does, yay!).

pd.DataFrame(U @ Sm @ Vt).head(5)| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 8.0 | 6.0 | 48.0 | 28.0 |

| 1 | 2.0 | 4.0 | 8.0 | 12.0 |

| 2 | 1.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 8.0 |

| 3 | 9.0 | 3.0 | 27.0 | 24.0 |

| 4 | 9.0 | 8.0 | 72.0 | 34.0 |

Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and Singular Value Decomposition (SVD) can be easily mixed up, especially when you have to keep track of so many acronyms. Here is a quick summary:

Let’s summarize first the steps to obtain Principal Components via SVD:

X = X - np.mean(X, axis = 0)X = (X - np.mean(X, axis = 0)) / np.std(X, axis = 0)After centering the original data matrix \(X\) so that each column has a mean of 0, we find its SVD: \[ X = U S V^T \]

Because \(X\) is centered, the covariance matrix of \(X\), \(\Sigma\), is equal to \(\frac{1}{n}X^T X\). Rearranging this equation, we get

\[ \begin{align} \Sigma &= \frac{1}{n}X^T X \\ &= \frac{1}{n}(U S V^T)^T U S V^T \\ &= \frac{1}{n}V S^T U^T U S V^T & \text{U is orthonormal, so $U^T U = I$} \\ &= \frac{1}{n}V S^2 V^T \end{align} \]

Multiplying both sides by \(V\), we get

\[ \begin{align} \Sigma V &= \frac{1}{n}VS^2 V^T V \\ &= \frac{1}{n}V S^2 \end{align} \]

This shows that the columns of \(V\) are the eigenvectors of the covariance matrix \(\Sigma\) and, therefore, the principal components. Additionally, the squared singular values \(S^2\) (divided by \(n\)) are the eigenvalues of \(\Sigma\).

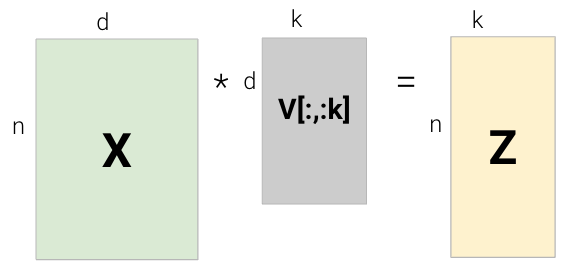

We’ve now shown that the first \(k\) columns of \(V\) (equivalently, the first \(k\) rows of \(V^{T}\)) are the first k principal components of \(X\). We can use them to construct the latent vector representation of \(X\), \(Z\), by projecting \(X\) onto the principal components.

We also have a second way of computing \(Z\) as follows:

\[ \begin{align} Z &= X V \\ &= USV^T V \\ &= U S \end{align} \]

\[Z = XV = US\]

In other words, we can construct \(X\)’s’ latent vector representation \(Z\) through:

Using \(Z\), we can approximately recover the centered \(X\) matrix by multiplying \(Z\) by \(V^T\): \[ Z V^T = XV V^T = USV^T = X\]

If we choose a k that is less than the rank of X then we will only recover X approximately. Note that to recover the original (uncentered) \(X\) matrix, we would also need to add back the mean.

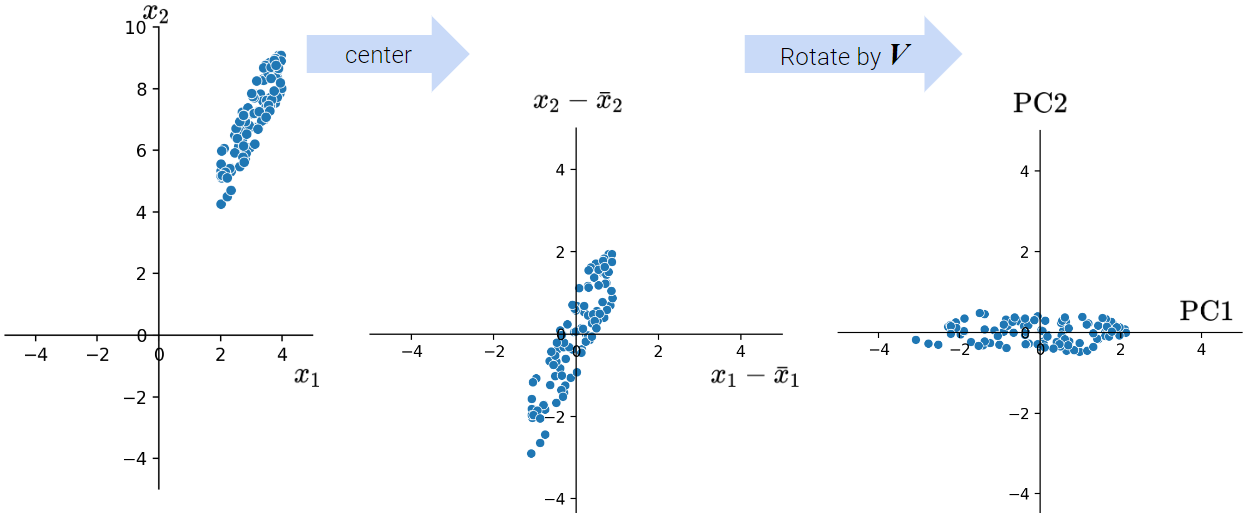

As we discussed above, when conducting PCA, we first center the data matrix \(X\) and then rotate it such that the direction with the most variation (i.e., the direction that is most spread out) aligns with the x-axis.

In particular, the elements of each principal component or column of \(V\) (row of \(V^{T}\)) rotate the original feature vectors, projecting \(X\) onto the principal components. The first column of \(V\) indicates how each feature contributes (e.g. positive, negative, etc.) to the first latent factor; it essentially assigns “weights” to each feature.

Coupled together, this interpretation also allows us to understand that:

Let’s now walk through an example where we compute PCA using SVD. In order to get the first \(k\) principal components from an \(n \times d\) matrix \(X\), we:

axis=0 so that the mean is computed per column.centered_df = rectangle - np.mean(rectangle, axis=0)

centered_df.head(5)| width | height | area | perimeter | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 2.97 | 1.35 | 24.78 | 8.64 |

| 1 | -3.03 | -0.65 | -15.22 | -7.36 |

| 2 | -4.03 | -1.65 | -20.22 | -11.36 |

| 3 | 3.97 | -1.65 | 3.78 | 4.64 |

| 4 | 3.97 | 3.35 | 48.78 | 14.64 |

U, S, Vt = np.linalg.svd(centered_df, full_matrices=False)

Sm = pd.DataFrame(np.diag(np.round(S, 1)))two_PCs = Vt.T[:, :2]

pd.DataFrame(two_PCs).head()| 0 | 1 | |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | -0.098631 | 0.668460 |

| 1 | -0.072956 | -0.374186 |

| 2 | -0.931226 | -0.258375 |

| 3 | -0.343173 | 0.588548 |

We define the total variance of a data matrix as the sum of variances of attributes. The principal components are a low-dimension representation that capture as much of the original data’s total variance as possible. Formally, the \(i\)-th singular value tells us the component score, or how much of the data variance is captured by the \(i\)-th principal component. Assuming the number of datapoints is \(n\):

\[\text{i-th component score} = \frac{(\text{i-th singular value}^2)}{n}\]

Summing up the component scores is equivalent to computing the total variance if we center our data.

If you want to dive deeper into PCA, Steve Brunton’s SVD Video Series is a great resource.

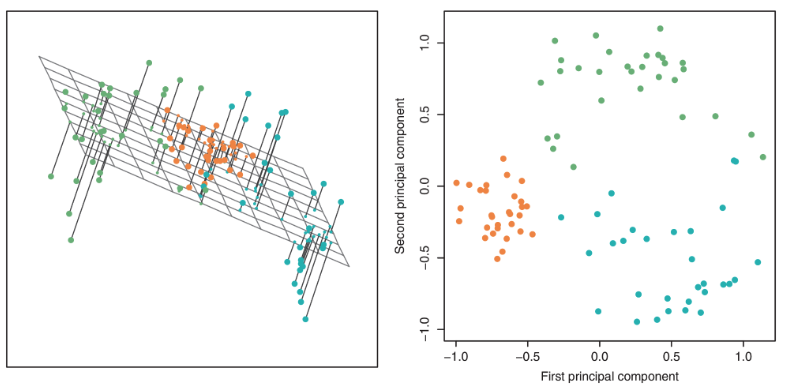

We often plot the first two principal components using a scatter plot, with PC1 on the \(x\)-axis and PC2 on the \(y\)-axis. This is often called a PCA plot.

If the first two singular values are large and all others are small, then two dimensions are enough to describe most of what distinguishes one observation from another. If not, a PCA plot omits a lot of information.

PCA plots help us assess similarities between our data points and if there are any clusters in our dataset. Here is one example:

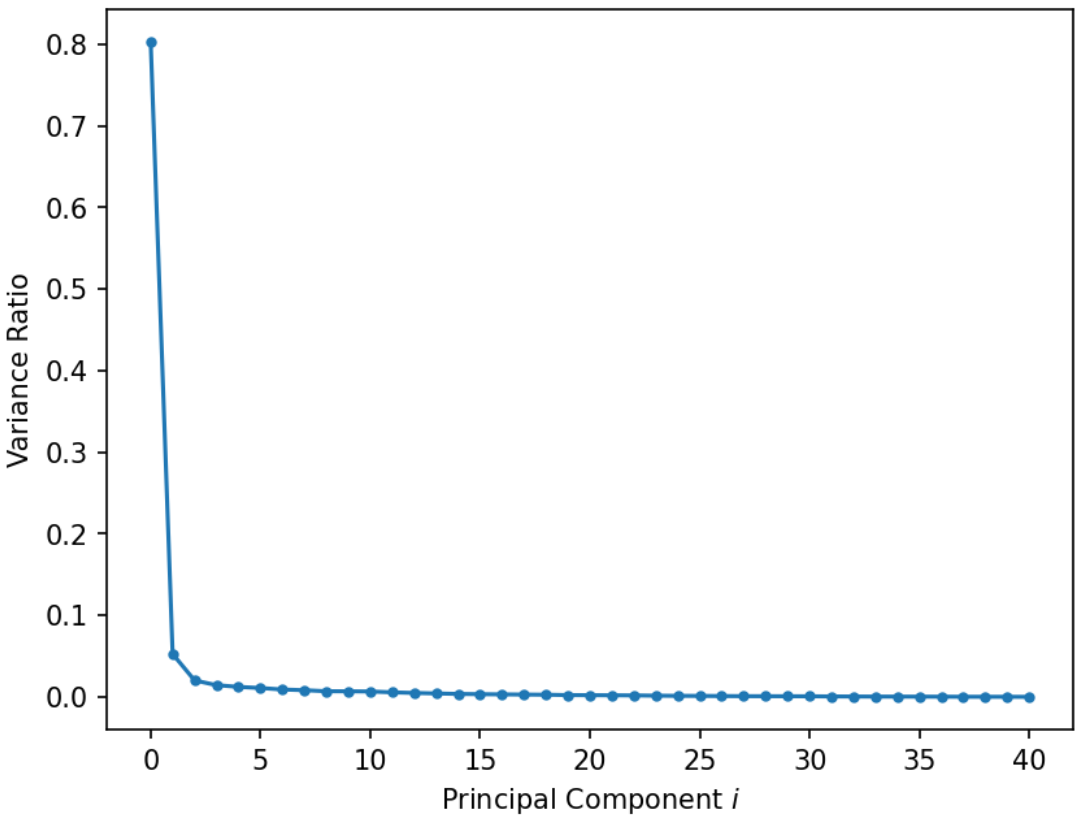

A scree plot shows the variance ratio captured by each principal component, with the largest variance ratio first. Recall that we could use each singular value to determine the component score:

\[\text{i-th component score} = \frac{(\text{i-th singular value}^2)}{n} = \frac{{s_i}^2}{N}\]

Therefore, the total variance is the sum of all component scores: \[\text{Total Variance} = \sum_{i=1}^{k} \frac{{s_i}^2}{N}\]

Then the variance ratio, or the proportion of fraction of total variance represented by a single principal component is the following: \[\text{Variance Ratio of Principal Component j} = \frac{\frac{{s_j}^2}{N}}{\sum_{i=1}^{k} \frac{{s_i}^2}{N}} = \frac{{s_j}^2}{\sum_{i=1}^{k} {s_i}^2}\]

In other words, the variance ratio is a principal component’s singular value squared divided by the sum of all singular values squared. Scree plots can help us visually determine the number of dimensions needed to describe the data reasonably. The singular values that fall in the region of the plot after a large drop-off correspond to principal components that are not needed to describe the data since they explain a relatively low proportion of the total variance of the data. This point where adding more principal components results in diminishing returns is called the “elbow” and is the point just before the line flattens out. Using this “elbow method”, we can see that the elbow is at the second principal component, so two dimensions are enough to describe most of what distinguishes one observation from another. If this was not the case, then a PCA scatter plot is omitting lots of information.

Interpreting this graph, first principal component explains 80% of the total variance in the data.

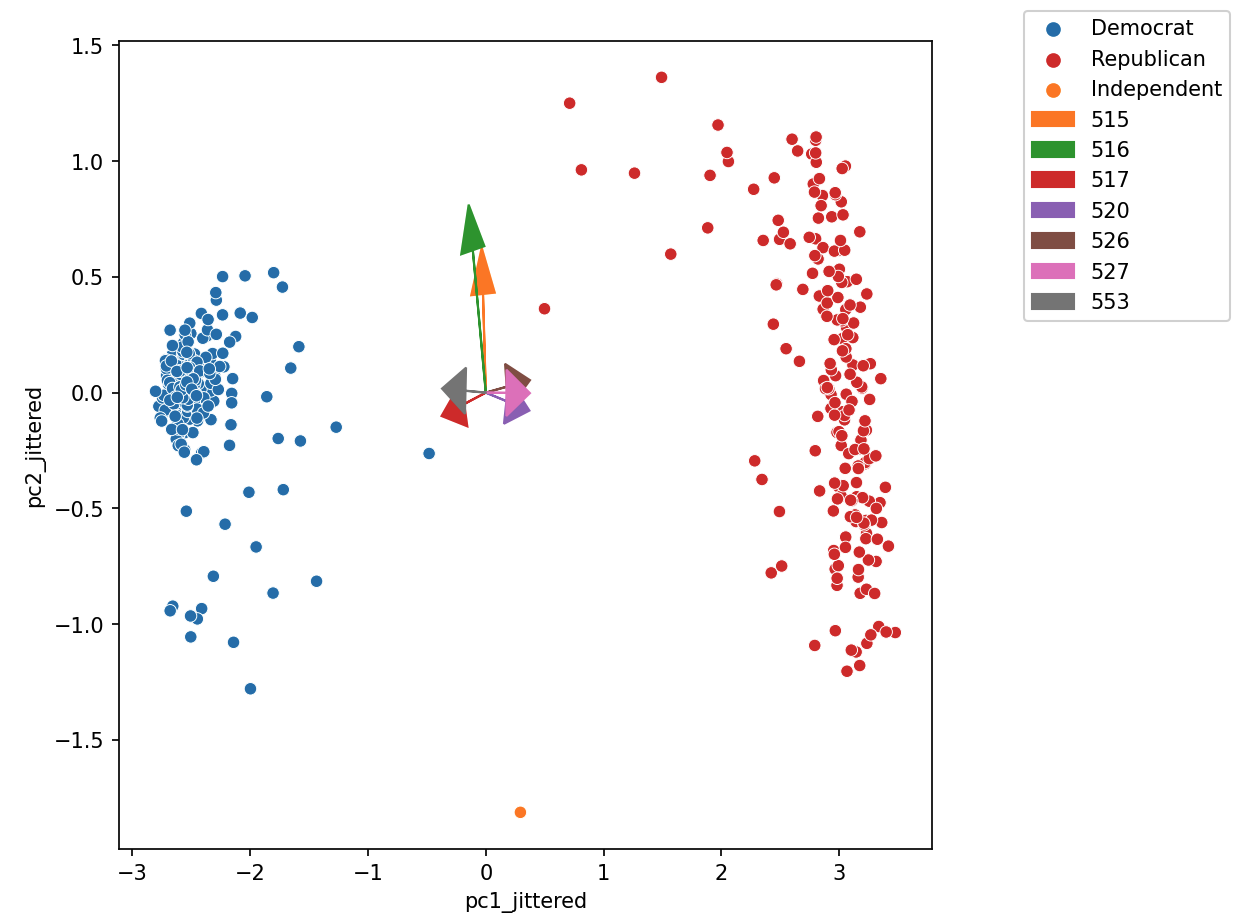

Biplots superimpose the directions onto the plot of PC1 vs. PC2, where vector \(j\) corresponds to the direction for feature \(j\) (e.g., \(v_{1j}, v_{2j}\)). There are several ways to scale biplot vectors — in this course, we plot the direction itself. For other scalings, which can lead to more interpretable directions/loadings, see SAS biplots.

Through biplots, we can interpret how features correlate with the principal components shown: positively, negatively, or not much at all.

The directions of the arrow are (\(v_1\), \(v_2\)), where \(v_1\) and \(v_2\) are how that specific feature column contributes to PC1 and PC2, respectively. \(v_1\) and \(v_2\) are elements of the first and second columns of \(V\), respectively (i.e., the first two rows of \(V^T\)).

Say we were considering feature 3, and say that was the purple arrow labeled “520” here (pointing bottom right).

Let’s examine how the House of Representatives (of the 116th Congress, 1st session) voted in the month of September 2019.

Specifically, we’ll look at the records of Roll call votes. From the U.S. Senate (link): roll call votes occur when a representative or senator votes “yea” or “nay” so that the names of members voting on each side are recorded. A voice vote is a vote in which those in favor or against a measure say “yea” or “nay,” respectively, without the names or tallies of members voting on each side being recorded.

import pandas as pd

import seaborn as sns

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import numpy as np

import yaml

from datetime import datetime

import plotly.express as px

import plotly.graph_objects as go

votes = pd.read_csv("data/votes.csv")

votes = votes.astype({"roll call": str})

votes.head()| chamber | session | roll call | member | vote | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | House | 1 | 555 | A000374 | Not Voting |

| 1 | House | 1 | 555 | A000370 | Yes |

| 2 | House | 1 | 555 | A000055 | No |

| 3 | House | 1 | 555 | A000371 | Yes |

| 4 | House | 1 | 555 | A000372 | No |

Suppose we pivot this table to group each legislator and their voting pattern across every (roll call) vote in this month. We mark 1 if the legislator voted Yes (“yea”), and 0 otherwise (“No”, “nay”, no vote, speaker, etc.).

def was_yes(s):

return 1 if s.iloc[0] == "Yes" else 0

vote_pivot = votes.pivot_table(

index="member", columns="roll call", values="vote", aggfunc=was_yes, fill_value=0

)

print(vote_pivot.shape)

vote_pivot.head()(441, 41)| roll call | 515 | 516 | 517 | 518 | 519 | 520 | 521 | 522 | 523 | 524 | ... | 546 | 547 | 548 | 549 | 550 | 551 | 552 | 553 | 554 | 555 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| member | |||||||||||||||||||||

| A000055 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ... | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| A000367 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ... | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| A000369 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ... | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| A000370 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ... | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| A000371 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ... | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

5 rows × 41 columns

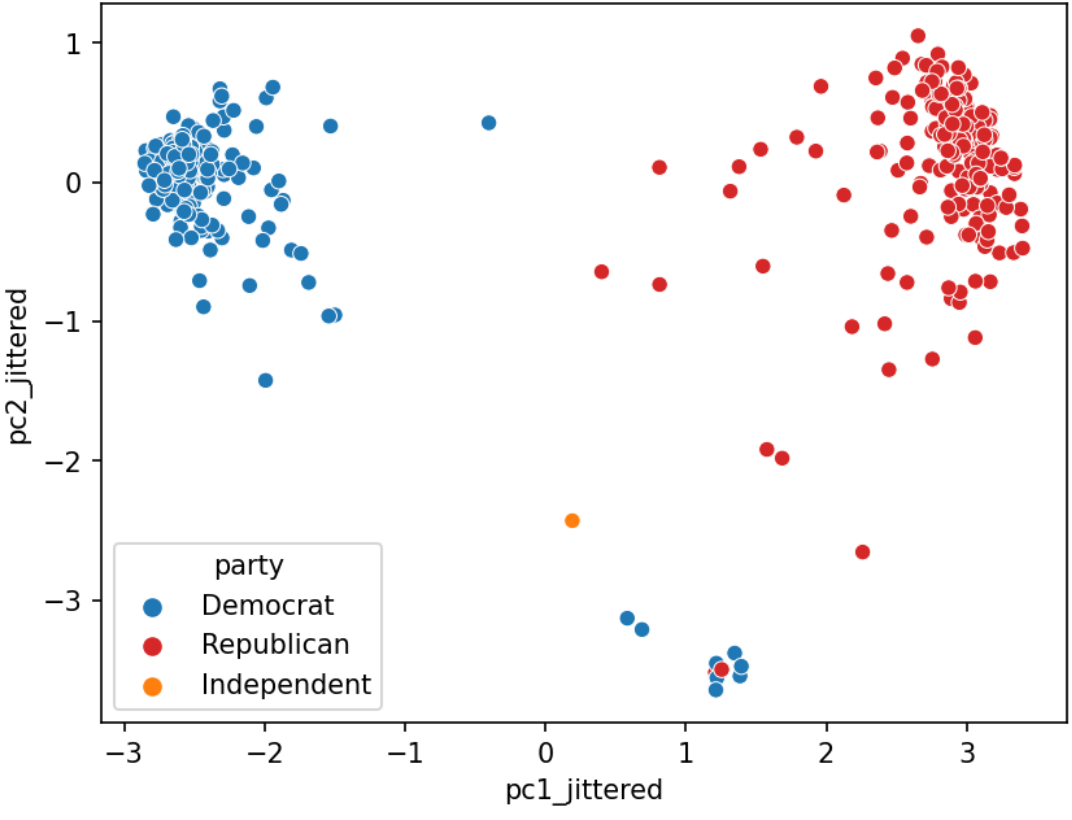

Do legislators’ roll call votes show a relationship with their political party?

While we could consider loading information about the legislator, such as their party, and see how this relates to their voting pattern, it turns out that we can do a lot with PCA to cluster legislators by how they vote. Let’s calculate the principal components using the SVD method.

vote_pivot_centered = vote_pivot - np.mean(vote_pivot, axis=0)

u, s, vt = np.linalg.svd(vote_pivot_centered, full_matrices=False) # SVDWe can use the singular values in s to construct a scree plot:

fig = px.line(y=s**2 / sum(s**2), title='Variance Explained', width=700, height=600, markers=True)

fig.update_xaxes(title_text='Principal Component i')

fig.update_yaxes(title_text='Proportion of Variance Explained')It looks like this graph plateaus after the third principal component, so our “elbow” is at PC3, and most of the variance is captured by just the first three principal components. Let’s use these PCs to visualize the latent vector representation of \(X\)!

# Calculate the latent vector representation (US or XV)

# using the first 3 principal components

vote_2d = pd.DataFrame(index=vote_pivot_centered.index)

vote_2d[["z1", "z2", "z3"]] = (u * s)[:, :3]

# Plot the latent vector representation

fig = px.scatter_3d(vote_2d, x='z1', y='z2', z='z3', title='Vote Data', width=800, height=600)

fig.update_traces(marker=dict(size=5))Baesd on the plot above, it looks like there are two clusters of datapoints. What do you think this corresponds to?

By incorporating member information (source), we can augment our graph with biographic data like each member’s party and gender.

legislators_data = yaml.safe_load(open("data/legislators-2019.yaml"))

def to_date(s):

return datetime.strptime(s, "%Y-%m-%d")

legs = pd.DataFrame(

columns=[

"leg_id",

"first",

"last",

"gender",

"state",

"chamber",

"party",

"birthday",

],

data=[

[

x["id"]["bioguide"],

x["name"]["first"],

x["name"]["last"],

x["bio"]["gender"],

x["terms"][-1]["state"],

x["terms"][-1]["type"],

x["terms"][-1]["party"],

to_date(x["bio"]["birthday"]),

]

for x in legislators_data

],

)

legs["age"] = 2024 - legs["birthday"].dt.year

legs.set_index("leg_id")

legs.sort_index()

vote_2d = vote_2d.join(legs.set_index("leg_id")).dropna()

np.random.seed(42)

vote_2d["z1_jittered"] = vote_2d["z1"] + np.random.normal(0, 0.1, len(vote_2d))

vote_2d["z2_jittered"] = vote_2d["z2"] + np.random.normal(0, 0.1, len(vote_2d))

vote_2d["z3_jittered"] = vote_2d["z3"] + np.random.normal(0, 0.1, len(vote_2d))

px.scatter_3d(vote_2d, x='z1_jittered', y='z2_jittered', z='z3_jittered', color='party', symbol="gender", size='age',

title='Vote Data', width=800, height=600, size_max=10,

opacity = 0.7,

color_discrete_map={'Democrat':'blue', 'Republican':'red', "Independent": "green"},

hover_data=['first', 'last', 'state', 'party', 'gender', 'age'])Using SVD and PCA, we can clearly see a separation between the red dots (Republican) and blue dots (Deomcrat).

We can also look at \(V^T\) directly to try to gain insight into why each component is as it is.

fig_eig = px.bar(x=vote_pivot_centered.columns, y=vt[0, :])

# extract the trace from the figure

fig_eig.show()We have the party affiliation labels so we can see if this eigenvector aligns with one of the parties.

party_line_votes = (

vote_pivot_centered.join(legs.set_index("leg_id")["party"])

.groupby("party")

.mean()

.T.reset_index()

.rename(columns={"index": "call"})

.melt("call")

)

fig = px.bar(

party_line_votes,

x="call", y="value", facet_row = "party", color="party",

color_discrete_map={'Democrat':'blue', 'Republican':'red', "Independent": "green"})

fig.for_each_annotation(lambda a: a.update(text=a.text.split("=")[-1]))loadings = pd.DataFrame(

{"pc1": np.sqrt(s[0]) * vt[0, :], "pc2": np.sqrt(s[1]) * vt[1, :]},

index=vote_pivot_centered.columns,

)

vote_2d["num votes"] = votes[votes["vote"].isin(["Yes", "No"])].groupby("member").size()

vote_2d.dropna(inplace=True)

fig = px.scatter(

vote_2d,

x='z1_jittered',

y='z2_jittered',

color='party',

symbol="gender",

size='num votes',

title='Biplot',

width=800,

height=600,

size_max=10,

opacity = 0.7,

color_discrete_map={'Democrat':'blue', 'Republican':'red', "Independent": "green"},

hover_data=['first', 'last', 'state', 'party', 'gender', 'age'])

for (call, pc1, pc2) in loadings.head(20).itertuples():

fig.add_scatter(x=[0,pc1], y=[0,pc2], name=call,

mode='lines+markers', textposition='top right',

marker= dict(size=10,symbol= "arrow-bar-up", angleref="previous"))

figEach roll call from the 116th Congress - 1st Session: https://clerk.house.gov/evs/2019/ROLL_500.asp

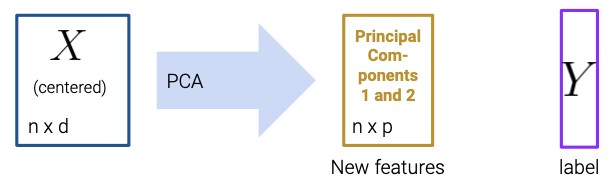

As shown in the demo, the primary goal of PCA is to transform observations from high-dimensional data down to low dimensions through linear transformations.

In machine learning, PCA is often used as a preprocessing step prior to training a supervised model.

Let’s explore how PCA is useful for building an image classification model based on the Fashion-MNIST dataset, a dataset containing images of articles of clothing; these images are gray scale with a size of 28 by 28 pixels. The copyright for Fashion-MNIST is held by Zalando SE. Fashion-MNIST is licensed under the MIT license.

First, we’ll load in the data.

import requests

from pathlib import Path

import time

import gzip

import os

import numpy as np

import plotly.express as px

def fetch_and_cache(data_url, file, data_dir="data", force=False):

"""

Download and cache a url and return the file object.

data_url: the web address to download

file: the file in which to save the results.

data_dir: (default="data") the location to save the data

force: if true the file is always re-downloaded

return: The pathlib.Path object representing the file.

"""

data_dir = Path(data_dir)

data_dir.mkdir(exist_ok=True)

file_path = data_dir / Path(file)

# If the file already exists and we want to force a download then

# delete the file first so that the creation date is correct.

if force and file_path.exists():

file_path.unlink()

if force or not file_path.exists():

print("Downloading...", end=" ")

resp = requests.get(data_url)

with file_path.open("wb") as f:

f.write(resp.content)

print("Done!")

last_modified_time = time.ctime(file_path.stat().st_mtime)

else:

last_modified_time = time.ctime(file_path.stat().st_mtime)

print("Using cached version that was downloaded (UTC):", last_modified_time)

return file_path

def head(filename, lines=5):

"""

Returns the first few lines of a file.

filename: the name of the file to open

lines: the number of lines to include

return: A list of the first few lines from the file.

"""

from itertools import islice

with open(filename, "r") as f:

return list(islice(f, lines))

def load_data():

"""

Loads the Fashion-MNIST dataset.

This is a dataset of 60,000 28x28 grayscale images of 10 fashion categories,

along with a test set of 10,000 images. This dataset can be used as

a drop-in replacement for MNIST.

The classes are:

| Label | Description |

|:-----:|-------------|

| 0 | T-shirt/top |

| 1 | Trouser |

| 2 | Pullover |

| 3 | Dress |

| 4 | Coat |

| 5 | Sandal |

| 6 | Shirt |

| 7 | Sneaker |

| 8 | Bag |

| 9 | Ankle boot |

Returns:

Tuple of NumPy arrays: `(x_train, y_train), (x_test, y_test)`.

**x_train**: uint8 NumPy array of grayscale image data with shapes

`(60000, 28, 28)`, containing the training data.

**y_train**: uint8 NumPy array of labels (integers in range 0-9)

with shape `(60000,)` for the training data.

**x_test**: uint8 NumPy array of grayscale image data with shapes

(10000, 28, 28), containing the test data.

**y_test**: uint8 NumPy array of labels (integers in range 0-9)

with shape `(10000,)` for the test data.

Example:

(x_train, y_train), (x_test, y_test) = fashion_mnist.load_data()

assert x_train.shape == (60000, 28, 28)

assert x_test.shape == (10000, 28, 28)

assert y_train.shape == (60000,)

assert y_test.shape == (10000,)

License:

The copyright for Fashion-MNIST is held by Zalando SE.

Fashion-MNIST is licensed under the [MIT license](

https://github.com/zalandoresearch/fashion-mnist/blob/master/LICENSE).

"""

dirname = os.path.join("datasets", "fashion-mnist")

base = "https://storage.googleapis.com/tensorflow/tf-keras-datasets/"

files = [

"train-labels-idx1-ubyte.gz",

"train-images-idx3-ubyte.gz",

"t10k-labels-idx1-ubyte.gz",

"t10k-images-idx3-ubyte.gz",

]

paths = []

for fname in files:

paths.append(fetch_and_cache(base + fname, fname))

# paths.append(get_file(fname, origin=base + fname, cache_subdir=dirname))

with gzip.open(paths[0], "rb") as lbpath:

y_train = np.frombuffer(lbpath.read(), np.uint8, offset=8)

with gzip.open(paths[1], "rb") as imgpath:

x_train = np.frombuffer(imgpath.read(), np.uint8, offset=16).reshape(

len(y_train), 28, 28

)

with gzip.open(paths[2], "rb") as lbpath:

y_test = np.frombuffer(lbpath.read(), np.uint8, offset=8)

with gzip.open(paths[3], "rb") as imgpath:

x_test = np.frombuffer(imgpath.read(), np.uint8, offset=16).reshape(

len(y_test), 28, 28

)

return (x_train, y_train), (x_test, y_test)class_names = [

"T-shirt/top",

"Trouser",

"Pullover",

"Dress",

"Coat",

"Sandal",

"Shirt",

"Sneaker",

"Bag",

"Ankle boot",

]

class_dict = {i: class_name for i, class_name in enumerate(class_names)}

(train_images, train_labels), (test_images, test_labels) = load_data()

print("Training images", train_images.shape)

print("Test images", test_images.shape)

rng = np.random.default_rng(42)

n = 5000

sample_idx = rng.choice(np.arange(len(train_images)), size=n, replace=False)

# Invert and normalize the images so they look better

img_mat = -1 * train_images[sample_idx].astype(np.int16)

img_mat = (img_mat - img_mat.min()) / (img_mat.max() - img_mat.min())

images = pd.DataFrame(

{

"images": img_mat.tolist(),

"labels": train_labels[sample_idx],

"class": [class_dict[x] for x in train_labels[sample_idx]],

}

)Using cached version that was downloaded (UTC): Tue Dec 16 13:23:25 2025

Using cached version that was downloaded (UTC): Tue Dec 16 13:23:25 2025

Using cached version that was downloaded (UTC): Tue Dec 16 13:23:25 2025

Using cached version that was downloaded (UTC): Tue Dec 16 13:23:25 2025

Training images (60000, 28, 28)

Test images (10000, 28, 28)Let’s see what some of the images contained in this dataset look like.

def show_images(images, ncols=5, max_images=30):

# conver the subset of images into a n,28,28 matrix for facet visualization

img_mat = np.array(images.head(max_images)["images"].to_list())

fig = px.imshow(

img_mat,

color_continuous_scale="gray",

facet_col=0,

facet_col_wrap=ncols,

height=220 * int(np.ceil(len(images) / ncols)),

)

fig.update_layout(coloraxis_showscale=False)

# Extract the facet number and convert it back to the class label.

fig.for_each_annotation(

lambda a: a.update(text=images.iloc[int(a.text.split("=")[-1])]["class"])

)

return fig

fig = show_images(images.groupby("class", as_index=False).sample(2), ncols=6)

fig.show()Let’s break this down further and look at it by class, or the category of clothing:

print(class_dict)

show_images(images.groupby('class',as_index=False).sample(2), ncols=6){0: 'T-shirt/top', 1: 'Trouser', 2: 'Pullover', 3: 'Dress', 4: 'Coat', 5: 'Sandal', 6: 'Shirt', 7: 'Sneaker', 8: 'Bag', 9: 'Ankle boot'}As we can see, each 28x28 pixel image is labelled by the category of clothing it belongs to. Us humans can very easily look at these images and identify the type of clothing being displayed, even if the image is a little blurry. However, this task is less intuitive for machine learning models. To illustrate this, let’s take a small sample of the training data to see how the images above are represented in their raw format:

images.head()| images | labels | class | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | [[1.0, 1.0, 1.0, 1.0, 1.0, 1.0, 1.0, 1.0, 1.0,... | 3 | Dress |

| 1 | [[1.0, 1.0, 1.0, 1.0, 1.0, 1.0, 1.0, 1.0, 1.0,... | 4 | Coat |

| 2 | [[1.0, 1.0, 1.0, 1.0, 1.0, 1.0, 1.0, 1.0, 1.0,... | 0 | T-shirt/top |

| 3 | [[1.0, 1.0, 1.0, 1.0, 1.0, 0.996078431372549, ... | 2 | Pullover |

| 4 | [[1.0, 1.0, 1.0, 1.0, 1.0, 1.0, 1.0, 1.0, 1.0,... | 1 | Trouser |

Each row represents one image. Every image belongs to a "class" of clothing with it’s enumerated "label". In place of a typically displayed image, the raw data contains a 28x28 2D array of pixel values; each pixel value is a float between 0 and 1. If we just focus on the images, we get a 3D matrix. You can think of this as a matrix containing 2D images.

X = np.array(images["images"].to_list())

X.shape (5000, 28, 28)However, we’re not used to working with 3D matrices for our training data X. Typical training data expects a vector of features for each datapoint, not a matrix per datapoint. We can reshape our 3D matrix so that it fits our typical training data by “unrolling” the the 28x28 pixels into a single row vector containing 28*28 = 784 dimensions.

X = X.reshape(X.shape[0], -1)

X.shape(5000, 784)What we have now is 5000 datapoints that each have 784 features. That’s a lot of features! Not only would training a model on this data take a very long time, it’s also very likely that our matrix is linearly independent. PCA is a very good strategy to use in situations like these when there are lots of features, but we want to remove redundant information.

sklearnTo perform PCA, let’s begin by centering our data.

X = X - X.mean(axis=0)We can run PCA using sklearn’s PCA package.

from sklearn.decomposition import PCA

n_comps = 50

pca = PCA(n_components=n_comps)

pca.fit(X)PCA(n_components=50)In a Jupyter environment, please rerun this cell to show the HTML representation or trust the notebook.

| n_components | 50 | |

| copy | True | |

| whiten | False | |

| svd_solver | 'auto' | |

| tol | 0.0 | |

| iterated_power | 'auto' | |

| n_oversamples | 10 | |

| power_iteration_normalizer | 'auto' | |

| random_state | None |

Now that sklearn helped us find the principal components, let’s visualize a scree plot.

# Make a line plot and show markers

fig = px.line(y=pca.explained_variance_ratio_ * 100, markers=True)

fig.show()We can see that the line starts flattening out around 2 or 3, which suggests that most of the data is explained by just the first two or three dimensions. To illustrate this, let’s plot the first three principal components and the datapoints’ corresponding classes. Can you identify any patterns?

images[['z1', 'z2', 'z3']] = pca.transform(X)[:, :3]

fig = px.scatter_3d(images, x='z1', y='z2', z='z3', color='class', hover_data=['labels'],

width=1000, height=800)

# set marker size to 5

fig.update_traces(marker=dict(size=5))As we saw in the demos, we often perform PCA during the Exploratory Data Analysis (EDA) stage of our data science lifecycle (if we already know what to model, we probably don’t need PCA!). It helps us with:

PCA is commonly used in biomedical contexts, which have many named variables! It can be used to:

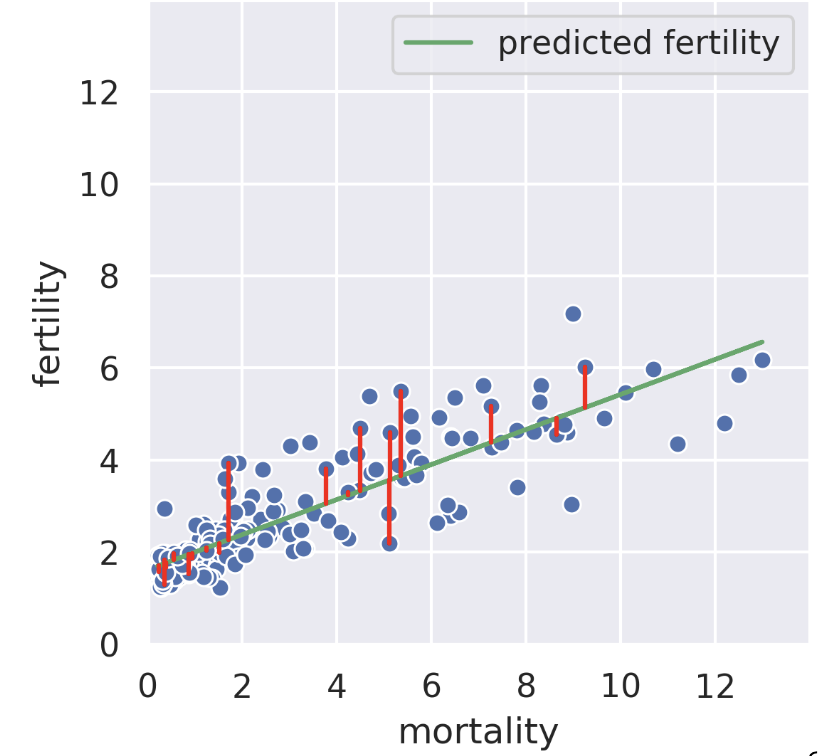

Suppose we know the child mortality rate of a given country. Linear regression tries to predict the fertility rate from the mortality rate; for example, if the mortality is 6, we might guess the fertility is near 4. The regression line tells us the “best” prediction of fertility given all possible mortality values by minimizing the root mean squared error. See the vertical red lines (note that only some are shown).

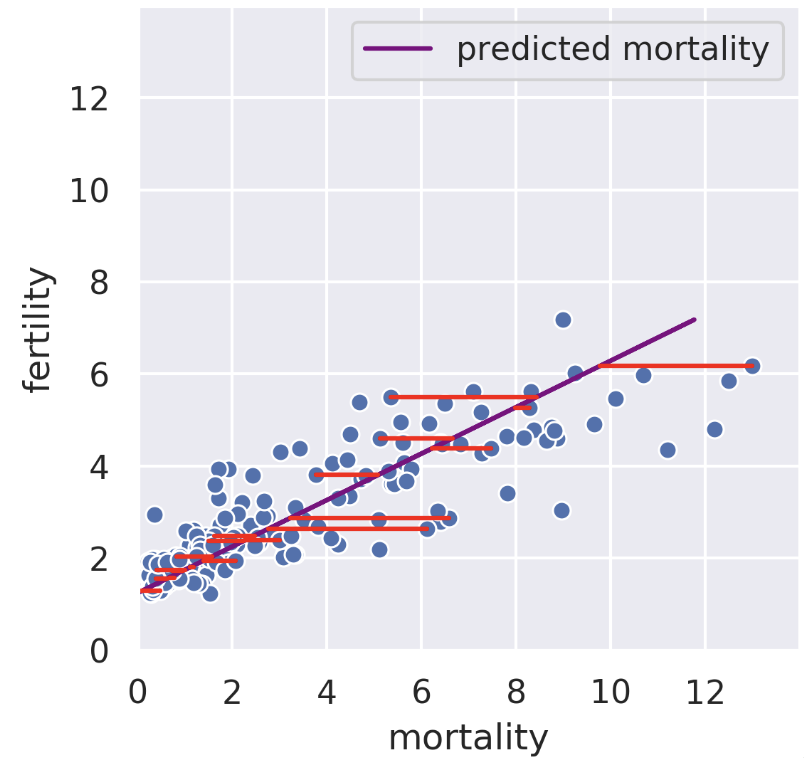

We can also perform a regression in the reverse direction. That is, given fertility, we try to predict mortality. In this case, we get a different regression line that minimizes the root mean squared length of the horizontal lines.

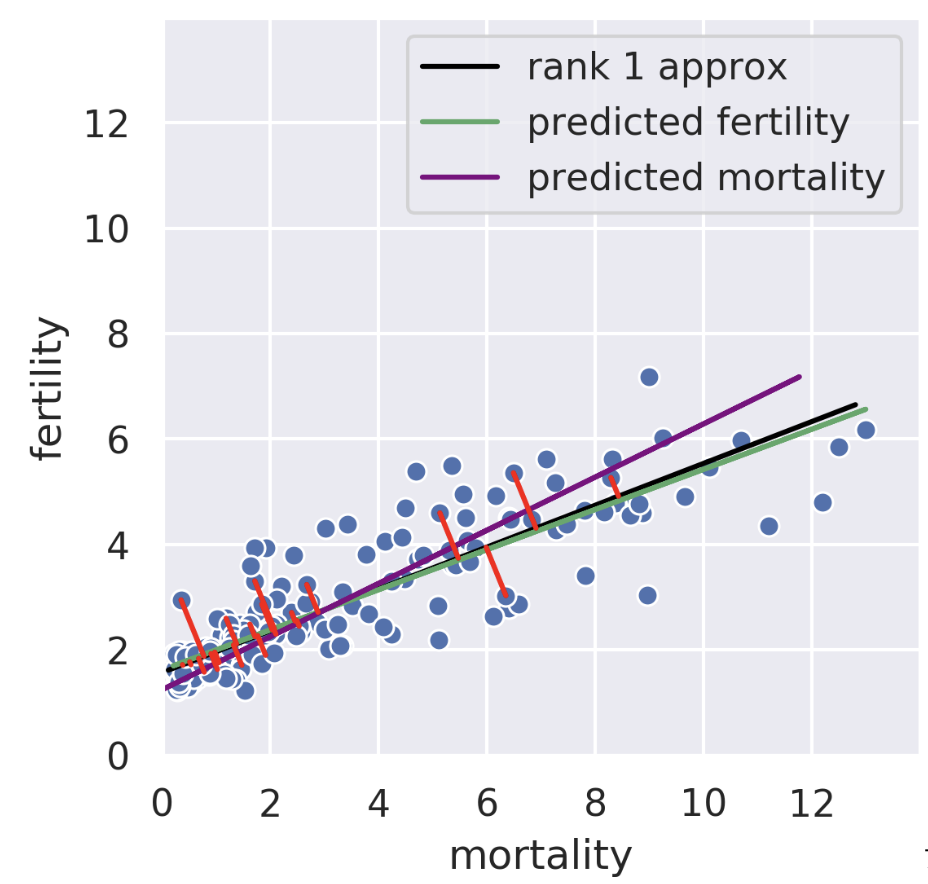

The rank-1 approximation is close but not the same as the mortality regression line. Instead of minimizing horizontal or vertical error, our rank-1 approximation minimizes the error perpendicular to the subspace onto which we’re projecting. That is, SVD finds the line such that if we project our data onto that line, the error between the projection and our original data is minimized. The similarity of the rank-1 approximation and the fertility was just a coincidence. Looking at adiposity and bicep size from our body measurements dataset, we see the 1D subspace onto which we are projecting is between the two regression lines.

Even in higher dimensions, the idea behind principal components is the same! Suppose we have 30-dimensional data and decide to use the first 5 principal components. Our procedure minimizes the error between the original 30-dimensional data and the projection of that 30-dimensional data onto the “best” 5-dimensional subspace. See CS 189 Note 10 for more details.

One key fact to remember is that the decomposition is not arbitrary. The rank of a matrix limits how small our inner dimensions can be if we want to perfectly recreate our matrix. The proof for this is out of scope.

Even if we know we have to factorize our matrix using an inner dimension of \(R\), that still leaves a large space of solutions to traverse. What if we have a procedure to automatically factorize a rank \(R\) matrix into an \(R\)-dimensional representation with some transformation matrix?

What if we wanted a 2D representation? It’s valuable to compress all of the data that is relevant into as few dimensions as possible in order to plot it efficiently. Some 2D matrices yield better approximations than others. How well can we do?

The proof defining component score is out of scope for this class, but it is included below for your convenience.

Setup: Consider the design matrix \(X \in \mathbb{R}^{n \times d}\), where the \(j\)-th column (corresponding to the \(j\)-th feature) is \(x_j \in \mathbb{R}^n\) and the element in row \(i\), column \(j\) is \(x_{ij}\). Further, define \(\tilde{X}\) as the centered design matrix. The \(j\)-th column is \(\tilde{x}_j \in \mathbb{R}^n\) and the element in row \(i\), column \(j\) is \(\tilde{x}_{ij} = x_{ij} - \bar{x_j}\), where \(\bar{x_j}\) is the mean of the \(x_j\) column vector from the original \(X\).

Variance: Construct the covariance matrix: \(\frac{1}{n} \tilde{X}^T \tilde{X} \in \mathbb{R}^{d \times d}\). The \(j\)-th element along the diagonal is the variance of the \(j\)-th column of the original design matrix \(X\):

\[\left( \frac{1}{n} \tilde{X}^T \tilde{X} \right)_{jj} = \frac{1}{n} \tilde{x}_j ^T \tilde{x}_j = \frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=i}^n (\tilde{x}_{ij} )^2 = \frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=i}^n (x_{ij} - \bar{x_j})^2\]

SVD: Suppose singular value decomposition of the centered design matrix \(\tilde{X}\) yields \(\tilde{X} = U S V^T\), where \(U \in \mathbb{R}^{n \times d}\) and \(V \in \mathbb{R}^{d \times d}\) are matrices with orthonormal columns, and \(S \in \mathbb{R}^{d \times d}\) is a diagonal matrix with singular values of \(\tilde{X}\).

\[ \begin{aligned} \tilde{X}^T \tilde{X} &= (U S V^T )^T (U S V^T) \\ &= V S U^T U S V^T & (S^T = S) \\ &= V S^2 V^T & (U^T U = I) \\ \frac{1}{n} \tilde{X}^T \tilde{X} &= \frac{1}{n} V S V^T =V \left( \frac{1}{n} S \right) V^T \\ \frac{1}{n} \tilde{X}^T \tilde{X} V &= V \left( \frac{1}{n} S \right) V^T V = V \left( \frac{1}{n} S \right) & \text{(right multiply by }V \rightarrow V^T V = I \text{)} \\ V^T \frac{1}{n} \tilde{X}^T \tilde{X} V &= V^T V \left( \frac{1}{n} S \right) = \frac{1}{n} S & \text{(left multiply by }V^T \rightarrow V^T V = I \text{)} \\ \left( \frac{1}{n} \tilde{X}^T \tilde{X} \right)_{jj} &= \frac{1}{n}S_j^2 & \text{(Define }S_j\text{ as the} j\text{-th singular value)} \\ \frac{1}{n} S_j^2 &= \frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=i}^n (x_{ij} - \bar{x_j})^2 \end{aligned} \]

The last line defines the \(j\)-th component score.