We continue learning tabular data abstraction, going over DataFrame and Index objects.

DataFrames and Indices¶

DataFrame¶

import pandas as pd

elections = pd.read_csv("data/elections.csv")

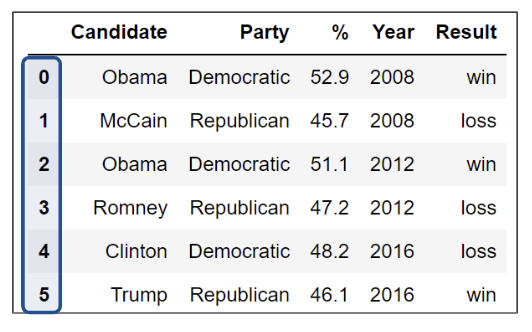

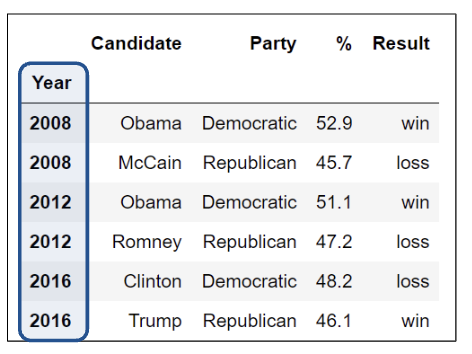

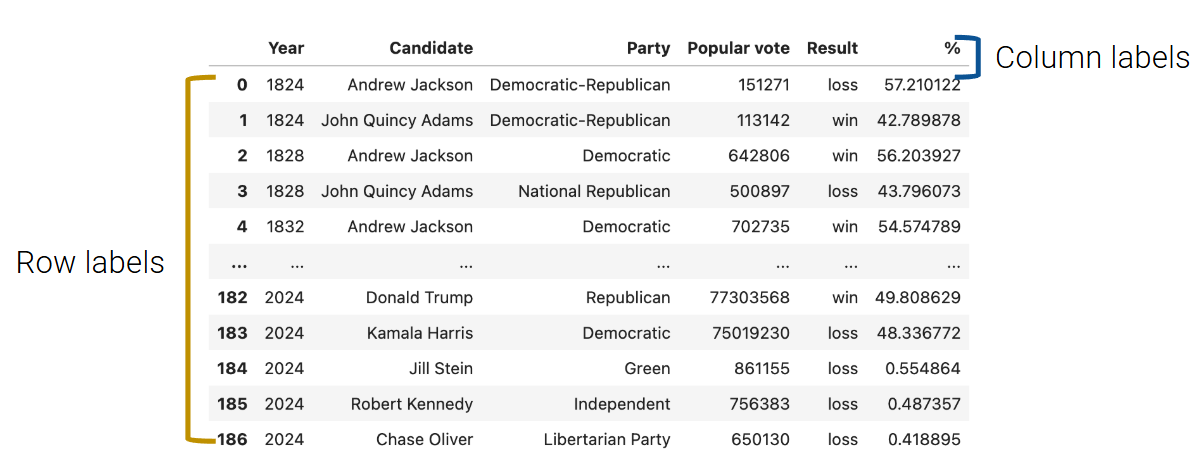

electionsThe code above code stores our DataFrame object in the elections variable. Upon inspection, our elections DataFrame has 182 rows and 6 columns (Year, Candidate, Party, Popular Vote, Result, %). Each row represents a single record — in our example, a presidential candidate from some particular year. Each column represents a single attribute or feature of the record.

Using a List and Column Name(s)¶

We’ll now explore creating a DataFrame with data of our own.

Consider the following examples. The first code cell creates a DataFrame with a single column Numbers.

df_list = pd.DataFrame([1, 2, 3], columns=["Numbers"])

df_listThe second creates a DataFrame with the columns Numbers and Description. Notice how a 2D list of values is required to initialize the second DataFrame — each nested list represents a single row of data.

df_list = pd.DataFrame([[1, "one"], [2, "two"]], columns = ["Number", "Description"])

df_listFrom a Dictionary¶

A third (and more common) way to create a DataFrame is with a dictionary. The dictionary keys represent the column names, and the dictionary values represent the column values.

Below are two ways of implementing this approach. The first is based on specifying the columns of the DataFrame, whereas the second is based on specifying the rows of the DataFrame.

df_dict = pd.DataFrame({

"Fruit": ["Strawberry", "Orange"],

"Price": [5.49, 3.99]

})

df_dictdf_dict = pd.DataFrame(

[

{"Fruit":"Strawberry", "Price":5.49},

{"Fruit": "Orange", "Price":3.99}

]

)

df_dictFrom a Series¶

Earlier, we explained how a Series was synonymous to a column in a DataFrame. It follows, then, that a DataFrame is equivalent to a collection of Series, which all share the same Index.

In fact, we can initialize a DataFrame by merging two or more Series. Consider the Series s_a and s_b.

# Notice how our indices, or row labels, are the same

s_a = pd.Series(["a1", "a2", "a3"], index = ["r1", "r2", "r3"])

s_b = pd.Series(["b1", "b2", "b3"], index = ["r1", "r2", "r3"])We can turn individual Series into a DataFrame using two common methods (shown below):

pd.DataFrame(s_a)s_b.to_frame()To merge the two Series and specify their column names, we use the following syntax:

pd.DataFrame({

"A-column": s_a,

"B-column": s_b

})Indices¶

On a more technical note, an index doesn’t have to be an integer, nor does it have to be unique. For example, we can set the index of the elections DataFrame to be the name of presidential candidates.

# Creating a DataFrame from a CSV file and specifying the index column

elections = pd.read_csv("data/elections.csv", index_col = "Candidate")

electionsWe can also select a new column and set it as the index of the DataFrame. For example, we can set the index of the elections DataFrame to represent the candidate’s party.

elections.reset_index(inplace = True) # Resetting the index so we can set it again

# This sets the index to the "Party" column

elections.set_index("Party")And, if we’d like, we can revert the index back to the default list of integers.

# This resets the index to be the default list of integer

elections.reset_index(inplace=True)

elections.indexRangeIndex(start=0, stop=187, step=1)It is also important to note that the row labels that constitute an index don’t have to be unique. While index values can be unique and numeric, acting as a row number, they can also be named and non-unique.

Here we see unique and numeric index values.

However, here the index values are not unique.

DataFrame Attributes: Index, Columns, and Shape¶

On the other hand, column names in a DataFrame are almost always unique. Looking back to the elections dataset, it wouldn’t make sense to have two columns named "Candidate". Sometimes, you’ll want to extract these different values, in particular, the list of row and column labels.

For index/row labels, use DataFrame.index:

elections.set_index("Party", inplace = True)

elections.indexIndex(['Democratic-Republican', 'Democratic-Republican', 'Democratic',

'National Republican', 'Democratic', 'National Republican',

'Anti-Masonic', 'Whig', 'Democratic', 'Whig',

...

'Green', 'Democratic', 'Republican', 'Libertarian', 'Green',

'Republican', 'Democratic', 'Green', 'Independent',

'Libertarian Party'],

dtype='object', name='Party', length=187)For column labels, use DataFrame.columns:

elections.columnsIndex(['index', 'Candidate', 'Year', 'Popular vote', 'Result', '%'], dtype='object')And for the shape of the DataFrame, we can use DataFrame.shape to get the number of rows followed by the number of columns:

elections.shape(187, 6)Slicing in DataFrames¶

Now that we’ve learned more about DataFrames, let’s dive deeper into their capabilities.

The API (Application Programming Interface) for the DataFrame class is enormous. In this section, we’ll discuss several methods of the DataFrame API that allow us to extract subsets of data.

The simplest way to manipulate a DataFrame is to extract a subset of rows and columns, known as slicing.

Common ways we may want to extract data are grabbing:

The first or last

nrows in theDataFrame.Data with a certain label.

Data at a certain position.

We will do so with four primary methods of the DataFrame class:

.headand.tail.loc.iloc[]

Extracting data with .head and .tail¶

The simplest scenario in which we want to extract data is when we simply want to select the first or last few rows of the DataFrame.

To extract the first n rows of a DataFrame df, we use the syntax df.head(n).

elections = pd.read_csv("data/elections.csv")# Extract the first 5 rows of the DataFrame

elections.head(5)Similarly, calling df.tail(n) allows us to extract the last n rows of the DataFrame.

# Extract the last 5 rows of the DataFrame

elections.tail(5)Label-based Extraction: Indexing with .loc¶

For the more complex task of extracting data with specific column or index labels, we can use .loc. The .loc accessor allows us to specify the labels of rows and columns we wish to extract. The labels (commonly referred to as the indices) are the bold text on the far left of a DataFrame, while the column labels are the column names found at the top of a DataFrame.

To grab data with .loc, we must specify the row and column label(s) where the data exists. The row labels are the first argument to the .loc function; the column labels are the second.

Arguments to .loc can be:

A single value.

A slice.

A list.

For example, to select a single value, we can select the row labeled 0 and the column labeled Candidate from the elections DataFrame.

elections.loc[0, 'Candidate']'Andrew Jackson'Keep in mind that passing in just one argument as a single value will produce a Series. Below, we’ve extracted a subset of the "Popular vote" column as a Series.

elections.loc[[87, 25, 179], "Popular vote"]87 15761254

25 848019

179 74216154

Name: Popular vote, dtype: int64Note that if we pass "Popular vote" as a list, the output will be a DataFrame.

elections.loc[[87, 25, 179], ["Popular vote"]]To select multiple rows and columns, we can use Python slice notation. Here, we select the rows from labels 0 to 3 and the columns from labels "Year" to "Popular vote". Notice that unlike Python slicing, .loc is inclusive of the right upper bound.

elections.loc[0:3, 'Year':'Popular vote']Suppose that instead, we want to extract all column values for the first four rows in the elections DataFrame. The shorthand : is useful for this.

elections.loc[0:3, :]We can use the same shorthand to extract all rows.

elections.loc[:, ["Year", "Candidate", "Result"]]There are a couple of things we should note. Firstly, unlike conventional Python, pandas allows us to slice string values (in our example, the column labels). Secondly, slicing with .loc is inclusive. Notice how our resulting DataFrame includes every row and column between and including the slice labels we specified.

Equivalently, we can use a list to obtain multiple rows and columns in our elections DataFrame.

elections.loc[[0, 1, 2, 3], ['Year', 'Candidate', 'Party', 'Popular vote']]Lastly, we can interchange list and slicing notation.

elections.loc[[0, 1, 2, 3], :]Integer-based Extraction: Indexing with .iloc¶

Slicing with .iloc works similarly to .loc. However, .iloc uses the index positions of rows and columns rather than the labels (think to yourself: loc uses lables; iloc uses indices). The arguments to the .iloc function also behave similarly — single values, lists, indices, and any combination of these are permitted.

Let’s begin reproducing our results from above. We’ll begin by selecting the first presidential candidate in our elections DataFrame:

# elections.loc[0, "Candidate"] - Previous approach

elections.iloc[0, 1]Notice how the first argument to both .loc and .iloc are the same. This is because the row with a label of 0 is conveniently in the (equivalently, the first position) of the elections DataFrame. Generally, this is true of any DataFrame where the row labels are incremented in ascending order from 0.

And, as before, if we were to pass in only one single value argument, our result would be a Series.

elections.iloc[[1,2,3],1]1 John Quincy Adams

2 Andrew Jackson

3 John Quincy Adams

Name: Candidate, dtype: objectHowever, when we select the first four rows and columns using .iloc, we notice something.

# elections.loc[0:3, 'Year':'Popular vote'] - Previous approach

elections.iloc[0:4, 0:4]Slicing is no longer inclusive in .iloc — it’s exclusive. In other words, the right end of a slice is not included when using .iloc. This is one of the subtleties of pandas syntax; you will get used to it with practice.

List behavior works just as expected.

#elections.loc[[0, 1, 2, 3], ['Year', 'Candidate', 'Party', 'Popular vote']] - Previous Approach

elections.iloc[[0, 1, 2, 3], [0, 1, 2, 3]]And just like with .loc, we can use a colon with .iloc to extract all rows or columns.

elections.iloc[:, 0:3]This discussion begs the question: when should we use .loc vs. .iloc? In most cases, .loc is generally safer to use. You can imagine .iloc may return incorrect values when applied to a dataset where the ordering of data can change. However, .iloc can still be useful — for example, if you are looking at a DataFrame of sorted movie earnings and want to get the median earnings for a given year, you can use .iloc to index into the middle.

Overall, it is important to remember that:

.locperformances label-based extraction..ilocperforms integer-based extraction.

Context-dependent Extraction: Indexing with []¶

The [] selection operator is the most baffling of all, yet the most commonly used. It only takes a single argument, which may be one of the following:

A slice of row numbers.

A list of column labels.

A single-column label.

That is, [] is context-dependent. Let’s see some examples.

A slice of row numbers¶

Say we wanted the first four rows of our elections DataFrame.

elections[0:4]A list of column labels¶

Suppose we now want the first four columns.

elections[["Year", "Candidate", "Party", "Popular vote"]]A single-column label¶

Lastly, [] allows us to extract only the "Candidate" column.

elections["Candidate"]0 Andrew Jackson

1 John Quincy Adams

2 Andrew Jackson

3 John Quincy Adams

4 Andrew Jackson

...

182 Donald Trump

183 Kamala Harris

184 Jill Stein

185 Robert Kennedy

186 Chase Oliver

Name: Candidate, Length: 187, dtype: objectThe output is a Series! In this course, we’ll become very comfortable with [], especially for selecting columns. In practice, [] is much more common than .loc, especially since it is far more concise.

Parting Note¶

The pandas library is enormous and contains many useful functions. Here is a link to its documentation. We certainly don’t expect you to memorize each and every method of the library, and we will give you a reference sheet for exams.

The introductory Data 100 pandas lectures will provide a high-level view of the key data structures and methods that will form the foundation of your pandas knowledge. A goal of this course is to help you build your familiarity with the real-world programming practice of ... Googling! Answers to your questions can be found in documentation, Stack Overflow, etc. Being able to search for, read, and implement documentation is an important life skill for any data scientist.

With that, we will move on to Pandas II!